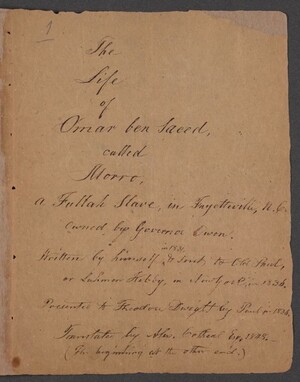

For the longest time, the documentation of African slavery in the United States has been reliant on the experiences and resources of White plantation owners and modern U.S. history textbooks written by White scholars. Due to the seemingly limited access to literacy for slaves, it was widely believed that Black perspective on slavery relied on oral accounts. The disparity of information between Black and White experiences remains vast, however, there are scholars and archivists who refuse to accept a one-sided narrative. In my experience of trying to research the documentation of African slavery in the U.S., the majority of primary resources available to the public are government papers on the sale and illnesses of slaves exchanged between white officials and owners. There were also documents by white abolitionists attempting to explain the need for change, but all of these archives lacked one very important feature: the voices of the enslaved.

What I personally appreciate about this archive is the “framing and discussion questions” they pose at the beginning of certain sections. I obviously had my own questions when I began my research, but these questions helped me narrow my lens of focus according to which source I was using. Including questions such as these is a major step in accessibility of archives to viewers of all ages and educational background. Many archives could benefit from this inclusive action and support a broader community’s curiosity. Exploring this archive has led me to the conclusion that literacy among slaves was not as uncommon as many historians have portrayed it to be. Within almost every oral narrative, the interviewee mentions the secret education of slaves by and within their own community. For example, in one of the archived narratives, Jenny Proctor, a former slave in Alabama, explained: “None of us was ’lowed to see a book or try to learn. Dey say we git smarter den dey was if we learn anything, but we slips around and gits hold of dat Webster’s old blue back speller and we hides it ’til way in de night and den we lights a little pine torch, and studies dat spellin’ book. We learn it too. I can read some now and write a little too.”

From my own experience, literacy training has been occurring for generations in Black communities. My grandmother taught my mother, who then taught me, a slave language that I originally thought was just a fun game to play. However, it actually was a method for slaves to learn how to spell without their master finding out and also a tool for safe communication. The literacy of Black slaves is also apparent in the abundance of letters exchanged between them. These letters have been transcribed onto pdf documents, but the original written documents are accessible via contacting the archive or using the citations included at the bottom of each letter.

An interesting observation on the materials found in this archive is the process of transcription. In most of the oral narratives, regardless of subject, the dialects of the speaker is reflected in the transcription. The conjunctions and truncations of words do not follow the contemporary “standard” of written English, but why must a “standard” be upheld when its conventions were created by the very people who caused the speaker to receive little to no “standard” English education? The hypocrisy of “correcting” a former slaves’ grammar would be glaringly clear, so it is vital that sources of this kind maintain objectivity and allow the voice of the speaker to remain heard in its entirety. In the past many white scholars and archivists have “corrected” the language of an interview in order to make it more accessible to modern, and often white, audiences. However, the way in which a story is told is just as important as the story itself. If you would like to explore more of the sources in the Black American archives on slavery, check out National Humanities Center’s “The Making of African American Identity”.

Contact me, Jessica Salow, with feedback at Jessica.Salow@asu.edu, as I would love to hear from you your thoughts regarding the work we here at ASU are doing in community archiving around Arizona. We also want your feedback on what you would like to see from us in future blog posts. And if you would like regular updates from the CDA team please follow our CDA Facebook page or the CDA Instagram page to keep abreast of the virtual events we are doing monthly. We have also made some changes to our website to better describe the community-driven archives initiative at ASU Library so please visit that page to learn more about our work or to connect with the rest of our team.

See you soon!