Simon Redington’s Bomb, published in 2008, is an homage to the strikingly beautiful language of “Bomb,” by Gregory Corso, re-conceptualized for the poem’s fiftieth anniversary. In collaboration with The Kamikaze Press, Redington breathes new life into this paramount, Beat piece through an artistry that prioritizes the impact of “Bomb” and its poetry through visual storytelling. The images which arrest us in the original composition are refigured to preserve, as well as add, new meanings to emotional parallels within “Bomb;” terror and ecstasy; mortification and bliss; sentience and insentience. Redington’s artistry straddles that thin line between devotion, “that I am unable to hate what is necessary to love” (110), and violence within “Bomb,” highlighting the duality that comes with wielding absolute power.

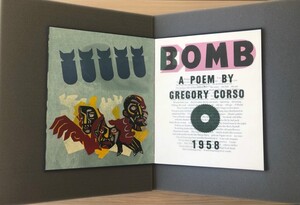

Embossed on the cover, “BOMB” is typed over a muted, ashy blue background. Color choice is indicative of what lies inside: a priority of white, red, and blue are cast as the main colors, to which the rest of Redington’s art operates around. Colors outside of the patriotic palette, such as yellow, pink, and black, symbolize shadows, or illumination, on the faces of those underneath the depicted bomb(s). These dynamic colors focalize Redington’s artistry on human expressions, the center of his homage.

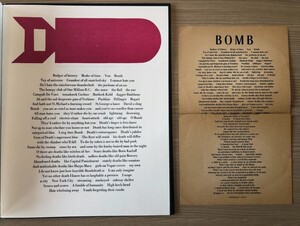

Instead of emphasizing the shape of the mushroom cloud, Redington’s Bomb splits the concrete plume into separate sections. The accordion-style manuscript of 1958, published by San Francisco’s City Lights and a part of Gregory Corso’s The Happy Birthday of Death, is reformatted to fit the confines of Bomb. Whereas the lyric of “Bomb” is continuous through the rhythms and shape of the poem, Bomb prioritizes continuity through imagery. Verses in Bomb, such as “and two very long American songs/ and they wish there were more songs” (130-1) and “O resound thy tanky knees/ BOOM…” (165-6) are separated by different pages. The only point where the lines are abruptly cut, due to the formatting of Corso’s “Bomb,” takes place at lines 124-5: “Happily so for if I felt bombs were caterpillars/I’d doubt not they’d become butterflies.” This splicing of Corso’s poem, by Redington, reshapes its visual format and lets us engage with Corso’s paramount work in a newfound manner.

We are placed into deeper historical and political contexts as well. Combinations, such as F-111, MK20, and BLU-17b are typed out in torrents across the pastedowns and flyleaves of Bomb. This typescript is not random: in fact, these letters and numbers reveal specific bombs (or bomber planes) deployed during the Vietnam War. We are swept away in this dual narrative, as the specific nomenclature for each bomb catalyzes the tangible destruction left behind.

In lieu of a written title for the 50th anniversary, the illustration of a bomb serves as a substitution for the word “bomb.” This pictorial ushers in the importance of symbols in Redington’s work. A translucent title page, accompanying the flyleaves before Corso’s poetry, layers language and image. Five, navy blue bombs, shades off from the light blue sky, are shown before the title page, alluding to the deep color as “Gem of Death’s supremest blue… ” (14). Underneath these bombs, the lurid expressions of three men, grasping towards the reader or sky, are shown.

Bodily contortions and facial expressions in Redington’s illustrations emphasize the rigidity of their stances. The limbs are rough, but furthermore, asks us to determine whether or not the hand is truly the hand. Could this apparatus be an object around the body, falling rubble, first flames to a fire, broken parts to a machine, or visually symbolized, arresting tension? When flipping through some of the pages with my own hand especially, I noticed a familiarity with both shapes: the tension in my own hand mirrored the tense, rigid hands in Redington’s illustration. These aspects are what makes this homage so powerful: our own collective humanity becomes a piece of (or even a part to) Bomb’s narrative.

The illustration following the end of “Bomb” shows a singular man cowering from a large, blue bomb. A union of hands merges man and mountain into a singular entity, beckoning to an attack on the land as synonymous with war on the body. To bomb the land is to bomb its people, undoubtedly a dark notion which Redington lays bare for us on this flyleaf. If one considers these hands as metaphors for landscape, then each hand serves a different purpose in crafting this image. The white hand, with a red outline on the grooves of its fingers, and contours to its palm, creates an abstract ice top to a mountain. The other two colors, yellow and red, could either add to the image of a fire, or maybe, a glow. The black hand extends around the face, shadow-like and covering the figure from an imminent BOOM. As there is only one head surrounded by a gaggle of hands, what else what is unseen in Redington’s art? What other meanings and interpretations can we find?

Redington’s storytelling through his art relays to us a fluid narrative that parallels the poetic prowess of “Bomb,” leading us visually through the momentous energy and profound message of Corso’s poem. Come see Bomb (part of ASU Library’s Rare Books and Manuscripts), by Simon Redington, at our Wurzburger Reading Room, located on the first floor of Hayden Library!

Alexa Nino, Distinctive Collections